What Banks Get Wrong About “Integrated” AI: MAS’s Proportionality Framework Decoded

November 18, 2025

Introduction

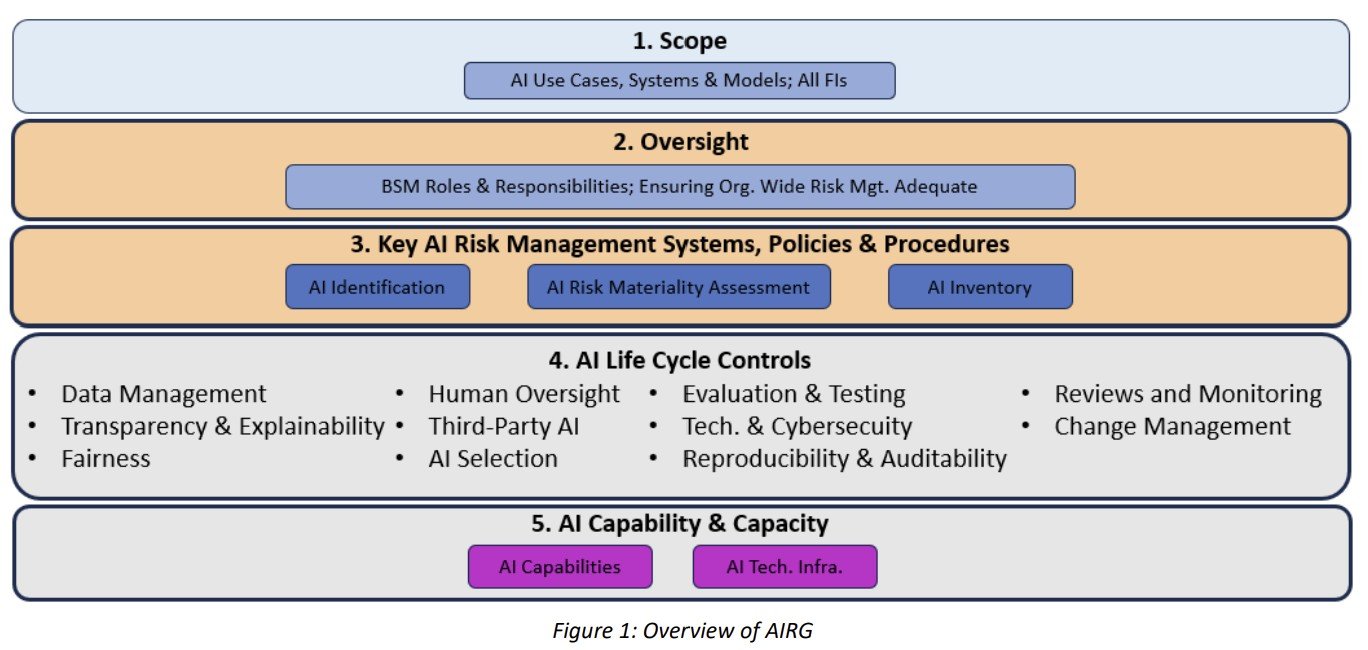

A subtle but profound distinction lies at the heart of the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s (MAS) new AI Risk Management Guidelines (AIRG): the difference between “integrated” and “assistive” AI [1]. While many financial institutions (FIs) believe their AI adoption is limited to benign, assistive tools, a closer reading of the MAS framework reveals a startling reality: most are already operating integrated AI systems without the requisite governance, risk management, and controls. This misclassification is not a mere semantic error; it is a critical compliance failure that exposes firms to significant regulatory scrutiny and unmitigated operational risks.

The MAS guidelines, issued for consultation in November 2025, move beyond the high-level principles that have characterized AI regulation to date. They introduce a practical, risk-based approach centered on a crucial question: would the lack of access to an AI tool disrupt a workflow the FI materially depends on? [1] If the answer is yes, the tool is not merely “assistive”—it is “integrated,” and the full weight of the AIRG applies. This seemingly simple test has profound implications, recasting many seemingly innocuous AI applications—from automated contract review to sophisticated data extraction tools—as core components of business processes that demand robust oversight.

This analysis decodes the MAS’s proportionality framework, exposing the common blind spots in how banks classify their AI usage. We will conduct a cross-jurisdictional comparison with the approaches in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong, perform a gap analysis to highlight the operational impacts of this misclassification, and provide actionable recommendations for Chief Compliance Officers and Heads of Operational Risk. The era of treating AI as a peripheral IT project is over; regulators now see it as a systemic force, and they expect FIs to manage it accordingly.

The Compliance/Risk Nexus: The Critical Line Between “Assistive” and “Integrated” AI

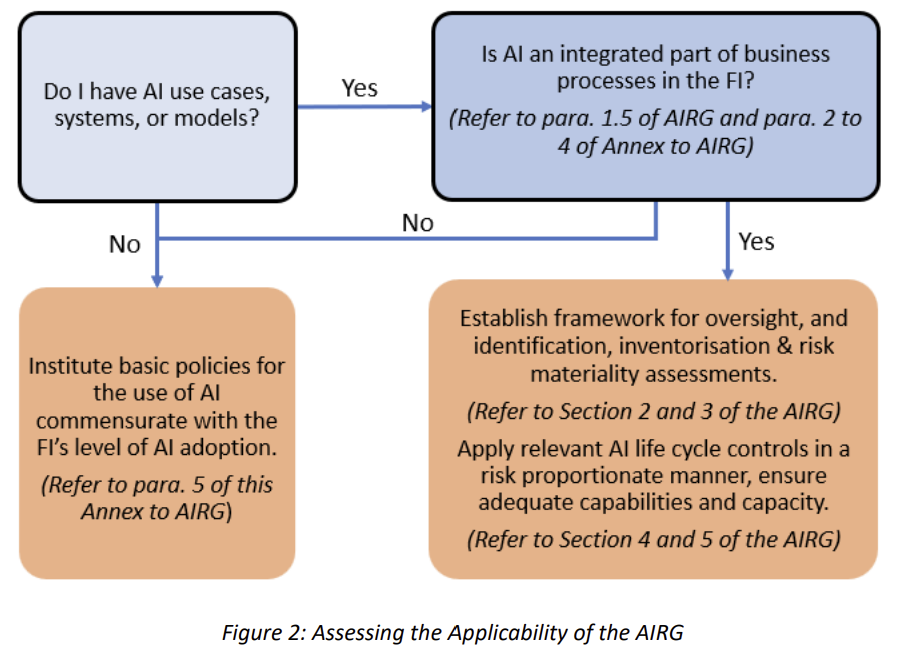

The core of the compliance challenge presented by the MAS AIRG lies in its nuanced definition of how AI is embedded within an organization. The guidelines create a two-tiered system of obligations based on a practical, impact-oriented assessment. While all FIs are expected to institute basic policies for AI use, the comprehensive framework—spanning detailed lifecycle controls, risk materiality assessments, and stringent governance—is triggered when AI becomes an “integrated part of business processes.” [1]

According to the annex of the consultation paper, AI is considered “integrated” if its absence would disrupt workflows an FI materially depends on, or if it is integrated with systems the FI materially relies on for its business activities. This moves the focus from the sophistication of the AI model itself to its role and impact within the operational fabric of the institution.

Many FIs mistakenly believe that because a human is “in the loop,” their AI systems are merely assistive. The MAS provides concrete examples that challenge this assumption. For instance, an AI-enabled financial data extraction tool used by a “substantial proportion of analysts” is deemed integrated because manual extraction would be “time-prohibitive.” [1] Similarly, an AI legal contract review tool used “systematically by the entire legal team” qualifies as integrated because its removal would “significantly slow contract review processes.” [1]

These examples reveal the regulator’s true focus: dependency and scale. The moment an AI tool transitions from a convenience for a few individuals to a standard process for a team or function, it crosses the threshold into “integrated” territory. The risk is no longer confined to a single user’s poor judgment but becomes a systemic operational dependency. If the AI system fails, the entire business process grinds to a halt or suffers significant degradation, creating precisely the kind of operational resilience risk that keeps regulators awake at night.

This distinction has immediate and far-reaching consequences for risk management. An “assistive” AI tool, such as a grammar checker, carries limited risk that can be managed through basic user training and oversight. An “integrated” AI system, however, introduces a host of complex risks that demand a structured, enterprise-wide response, as outlined in the table below.

| Risk Domain | Implications of “Assistive” AI | Implications of “Integrated” AI |

|---|---|---|

| Operational Resilience | Low impact; manual workarounds are feasible without significant disruption. | "High impact; system failure can halt critical business processes, leading to significant financial or reputational damage." |

| Model Risk Management | Limited scope; model failure affects a single user or task. | "Expanded scope; model drift, bias, or failure has systemic consequences, requiring a full MRM lifecycle approach." |

| Third-Party Risk | Standard vendor due diligence may suffice. | "Heightened due diligence required, focusing on concentration risk, data governance, and the vendor’s own AI risk management practices." |

| Conduct Risk | Contained risk of individual misconduct or error. | "Systemic risk of biased or unfair outcomes at scale (e.g., in credit or underwriting), attracting regulatory scrutiny." |

| Data Governance | Data usage is limited and controlled by the individual user. | "Requires robust data governance for training and operational data, including quality, lineage, and privacy controls." |

By failing to correctly classify their AI systems as “integrated,” FIs are operating with a dangerously incomplete view of their risk landscape. They are applying basic, user-level controls to systemic, enterprise-level risks—a gap that the MAS has now made explicitly clear it will no longer tolerate.

Cross-Jurisdictional Comparison: A Spectrum of Proportionality

The MAS’s detailed proportionality framework, with its clear distinction between “integrated” and “assistive” AI, represents a significant step forward in regulatory clarity. When compared with the approaches of other major financial hubs like the United Kingdom and Hong Kong, it becomes evident that while all three jurisdictions embrace a risk-based, proportionate approach, their definitions and implementation guidance vary significantly. This creates a complex compliance landscape for global FIs.

United Kingdom: A Principles-Based, Outcomes-Focused Approach

The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has deliberately avoided creating new, AI-specific regulations. Instead, it relies on its existing principles-based, technology-neutral framework to govern AI. The FCA’s stance, as articulated in its 2024 AI Update and its approach document updated in September 2025, is that its current rules and the five key principles of the UK government’s AI policy—safety, transparency, fairness, accountability, and contestability—are sufficient to mitigate the risks associated with AI [2] [3].

“We do not plan to introduce extra regulations for AI. Instead, we’ll rely on existing frameworks, which mitigate many of the risks associated with AI.” - FCA, AI and the FCA: our approach [2]

This approach offers maximum flexibility but lacks the granular guidance provided by the MAS. The UK framework does not offer a formal distinction equivalent to “integrated” versus “assistive.” Instead, the onus is on firms to interpret how existing regulations—such as the Senior Managers and Certification Regime (SMCR), the Consumer Duty, and operational resilience rules—apply to their specific AI use cases. While this promotes innovation, it also creates ambiguity. A firm’s assessment of proportionality is left to its own judgment, which may not align with the regulator’s expectations in a post-incident review. The lack of clear thresholds or examples means that UK-based FIs may be underestimating the regulatory expectations for their AI governance frameworks compared to their Singaporean counterparts.

Hong Kong: An Evolving, Principles-Driven Framework

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) has been a relatively early mover in AI regulation, issuing its “High-level Principles on Artificial Intelligence” in November 2019 [4]. This framework, built on 12 principles across governance, application design, and monitoring, also advocates for proportionate application based on AI usage and risk levels. However, like the UK’s approach, it does not provide a clear-cut definition of different tiers of AI integration.

The HKMA’s approach is characterized by its iterative nature, with subsequent circulars addressing specific AI applications, such as the use of AI for anti-money laundering (AML) monitoring in September 2024 and consumer protection in the context of Generative AI in August 2024 [5] [6]. This reflects a philosophy of applying its core principles to emerging technologies and risks as they arise. While the HKMA’s twin principles of “technology neutrality and risk-based supervision” align with the broader global consensus, the lack of a detailed proportionality framework like Singapore’s means that firms in Hong Kong must also rely more heavily on their own interpretation.

Comparative Analysis: The Value of Singapore’s Clarity

The following table summarizes the key differences in the proportionality frameworks of the three jurisdictions:

| Jurisdiction | Proportionality Framework | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Singapore (MAS) | Explicit, two-tiered model (“integrated” vs. “assistive”) | - Clear definitions and examples - Focus on operational dependency and scale - Triggers specific, comprehensive risk management obligations |

| United Kingdom (FCA) | Implicit, principles-based model | - Relies on existing, non-AI-specific regulations - High degree of flexibility and firm interpretation - No formal classification of AI use cases |

| Hong Kong (HKMA) | Evolving, principles-driven model | - Core set of high-level principles from 2019 - Proportionality based on usage and risk levels - Specific guidance issued for emerging AI applications |

For a global FI, the MAS’s approach, while more prescriptive, offers a significant advantage: clarity. The “integrated” vs. “assistive” distinction provides a concrete methodology for firms to self-assess their AI risk exposure and to implement the appropriate level of control. It removes the guesswork inherent in the UK and Hong Kong models, reducing the risk of a compliance gap stemming from a misinterpretation of regulatory expectations. The MAS has effectively provided a safe harbor of sorts: if a firm can demonstrate that its AI use is purely assistive and has implemented the basic required policies, it has a defensible position. Conversely, if its use is integrated, the path forward, while demanding, is clearly laid out.

This clarity forces a much-needed conversation within FIs about the true nature of their AI adoption. It pushes them to move beyond generic statements about “leveraging AI” and to conduct a rigorous, evidence-based assessment of their operational dependencies. In doing so, the MAS is not just setting a higher bar for AI risk management; it is providing the ladder to help firms reach it.

Gap Analysis & Operational Impact: The Unseen Risks of Misclassification

The failure to recognize the shift from “assistive” to “integrated” AI is not a theoretical problem; it creates immediate and substantial gaps in a financial institution’s risk and compliance frameworks. When an AI tool used for summarizing research becomes a standard part of the investment analysis workflow for an entire team, it is no longer a simple productivity aid. It is an integrated component of the investment decision-making process, and treating it otherwise is a form of willful blindness. This misclassification leads to critical deficiencies across multiple domains.

Operational Impact: A private bank's "assistive" GenAI tool for RMs is not monitored. Model drift causes it to start recommending unsuitable, high-risk products to a specific demographic. Because it's not in the MRM framework, the systemic conduct risk goes undetected until client complaints surge.

Operational Impact: A bank's "assistive" third-party AML tool receives a vendor update with a new blind spot. Complacent analysts approve flawed outputs. A major money laundering scheme passes through, and the bank is held accountable for failing to conduct adequate due diligence on the vendor's change management.

Operational Impact: An insurer's "assistive" claims tool is so efficient that human assessors, under pressure, begin to rubber-stamp its recommendations. A subtle bias in the AI systematically undervalues claims from a specific region, leading to unfair treatment of customers and a class-action lawsuit.

These examples demonstrate that the operational impact of misclassifying AI is not a matter of minor compliance infractions. It leads to systemic failures in risk management that can have severe financial, regulatory, and reputational consequences. The MAS guidelines are a clear signal that regulators expect firms to look beyond the superficial label of “assistive” and to confront the reality of their operational dependence on AI.

Strategic Implications & Forward-Looking View: Beyond Compliance to Competitive Advantage

The MAS’s sophisticated proportionality framework is more than just a new set of compliance hurdles; it is a strategic roadmap for the future of financial services. For forward-thinking institutions, these guidelines offer an opportunity to move beyond a reactive, compliance-focused posture and to build a robust AI governance capability that becomes a source of competitive advantage. The firms that master this new landscape will not only mitigate risk but will also be better positioned to innovate responsibly, attract talent, and earn the trust of customers and regulators alike.

The End of the AI “Wild West”

The era of ad-hoc, uncoordinated AI experimentation is definitively over. The MAS guidelines signal a broader global trend towards more structured and formalized AI governance. FIs that continue to treat AI as a series of disconnected IT projects, rather than as a systemic, enterprise-wide strategic capability, will find themselves perpetually on the back foot.

The Rise of the AI Risk Management Function

Just as the 2008 financial crisis led to the elevation of the Chief Risk Officer, the proliferation of integrated AI will necessitate the creation of a dedicated and empowered AI risk management function. Firms that invest in developing these capabilities internally will have a significant human capital advantage.

A New Paradigm for Vendor Relationships

The shift to integrated AI fundamentally alters the power dynamic between FIs and their technology vendors. The days of accepting opaque, “black box” AI solutions are numbered. FIs will need to build the technical expertise to challenge their vendors. This will lead to a flight to quality, where vendors who embrace transparency and robust governance will become preferred partners, while those who do not will be seen as an unacceptable risk.

Studio AM: Your Partner in Navigating the New AI Risk Landscape

The complexity of this new environment cannot be overstated. It requires a unique blend of regulatory expertise, technical knowledge, and strategic foresight. This is precisely where Studio AM provides value. We help our clients move beyond a check-the-box compliance exercise to build a sustainable AI risk management framework that enables responsible innovation. Our services are designed to address the critical gaps identified by the MAS guidelines:

In a world where AI is rapidly becoming a core component of the financial system, a reactive approach to risk management is a strategy for failure. The MAS has provided a clear vision of the future. Studio AM provides the expertise to help you thrive in it.

Actionable Recommendations: The Path Forward

For Chief Compliance Officers and Heads of Operational Risk, the MAS guidelines are a call to immediate action. The risk of regulatory sanction for non-compliance is real, but the greater risk is the unmanaged operational and reputational exposure from misclassified AI. The following is a phased, actionable plan to align your organization with the new reality of AI risk management.

- Initiate an Enterprise-Wide AI Census: Deploy a rapid, mandatory survey to all business heads to disclose all AI/ML tools.

- Form a Provisional AI Working Group: Assemble a cross-functional team (Compliance, Risk, Tech, Business) to triage findings.

- Brief the Board and Senior Management: Frame this as a strategic risk and compliance imperative to secure buy-in.

- Develop a Formal AI Classification Framework: Create a documented decision tree based on MAS dependency and scale criteria.

- Conduct a Formal Gap Analysis: Assess current controls for each "integrated" system against the MAS AIRG.

- Enhance Third-Party Risk Management: Immediately update vendor due diligence with AI-specific questions.

- Establish a Formal AI Governance Committee: Formalize the working group into a permanent committee with a clear charter.

- Integrate AI Risk into 3 Lines of Defense: Train and embed AI risk ownership in the business (1LOD), oversight in Risk/Compliance (2LOD), and assurance in Audit (3LOD).

- Implement Continuous Monitoring: Develop KRIs and dashboards for "integrated" systems to report to the committee.

By following this structured path, you can transform the challenge of the MAS guidelines into an opportunity to build a robust, future-proof AI risk management capability that will serve as a cornerstone of your institution’s long-term success.

References

[1] Monetary Authority of Singapore. (2025, November 13). Consultation Paper on Guidelines on Artificial Intelligence Risk Management. https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2025/mas-guidelines-for-artificial-intelligence-risk-management

[2] Financial Conduct Authority. (2025, September 9). AI and the FCA: our approach. https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/ai-approach

[3] Financial Conduct Authority. (2024). AI Update. https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/corporate/ai-update.pdf

[4] Hong Kong Monetary Authority. (2019, November 1). High-level Principles on Artificial Intelligence. https://brdr.hkma.gov.hk/eng/doc-ldg/docId/20191101-1-EN

[5] Hong Kong Monetary Authority. (2024, September 9). Use of Artificial Intelligence for Monitoring of Suspicious Activities. https://brdr.hkma.gov.hk/eng/doc-ldg/docId/20241122-3-EN

[6] Hong Kong Monetary Authority. (2024, August 19). Consumer Protection in respect of Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence. https://brdr.hkma.gov.hk/eng/doc-ldg/docId/20241107-1-EN