Prudential First: Canada’s Defensive Stance of Stablecoin Act vs. Global Models

December 5, 2025

Introduction

Canada's draft Stablecoin Act, released November 18, 2025, as Division 45 of Bill C-15, reveals a regulatory philosophy at odds with frameworks already implemented in Hong Kong, Singapore, and the European Union. [1] For compliance officers at banks, the differences matter: Canada has chosen a prudential regime under Bank of Canada oversight, not a licensing system for market access. This choice creates operational friction for cross-border stablecoin operations and demands jurisdiction-specific compliance protocols.

The Act defines a stablecoin as "a digital asset that is intended or designed to maintain a stable value relative to the value of one fiat currency" (Section 2). To issue in Canada, entities must apply to the Bank of Canada for inclusion on a public registry. No registry listing, no issuance (Section 15). This is central bank supervision of payment infrastructure, not securities regulation or consumer protection.

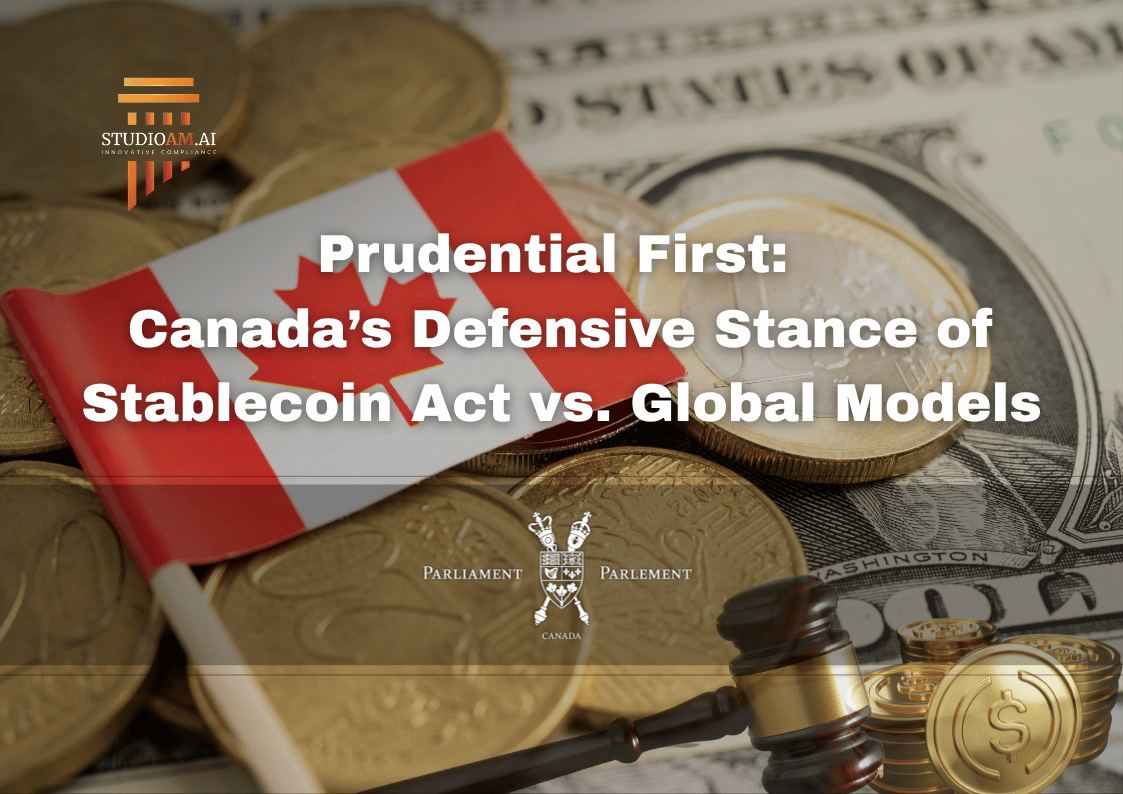

The Bankruptcy-Remote Mandate: Holder Protection Over Issuer Capital

Section 39(2)(b) of the Act requires issuers to ensure that reserve assets are held "in a manner that ensures that the assets are not available to satisfy creditors of the qualified custodian or the issuer, including under the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act...other than to satisfy any claims of the holders of a stablecoin with respect to the redemption of the stablecoin." [1] This is a creditor hierarchy intervention. The regulator is ring-fencing stablecoin reserves from other creditors' claims, even in insolvency.

Hong Kong's Stablecoins Ordinance, effective August 1, 2025, requires 100% reserve backing and expects overcollateralization to provide buffers against market volatility. [3] But Hong Kong does not mandate a bankruptcy-remote structure. Instead, it requires HK$25 million in paid-up share capital, HK$3 million in liquid capital, and excess liquid capital equal to 12 months of operating expenses. This is a capital adequacy approach: the issuer must have financial resilience to operate on an ongoing basis.

The EU's Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA), fully effective December 30, 2024, requires issuers of asset-referenced tokens (ARTs) to maintain minimum own funds equal to 2% of the average reserve amount. [5] This is also a capital adequacy requirement, not a bankruptcy-remote structure. The EU wants issuers to have "skin in the game" to absorb losses and reduce moral hazard.

(Image Generated by Notebook LM)

Canada's choice to forgo capital adequacy in favor of bankruptcy-remote reserves reflects a payment system protection model. The Bank of Canada is less concerned with issuer solvency than with ensuring stablecoin holders can recover funds even in a disorderly failure. For banks acting as qualified custodians under Section 39, this creates new legal and operational obligations: segregating assets, ensuring they are unavailable to creditors, and maintaining documentation to prove compliance.

The FRFI Exclusion: Implicit Trust in Existing Prudential Frameworks

Section 12 of the Act states: "Subject to the regulations, this Act does not apply to an issuer that is a financial institution." [1] Federally-regulated financial institutions (FRFIs)—banks, trust companies, insurance companies under OSFI supervision—are excluded from the Stablecoin Act. If they issue stablecoins, they do so under existing regulatory frameworks.

This exclusion reveals Canada's bank-centric regulatory philosophy. The Bank of Canada trusts OSFI-supervised institutions more than non-bank stablecoin issuers. Sections 3 and 4 clarify that stablecoin issuance under the Act does not constitute "dealing in securities" or "engaging in the business of accepting deposit liabilities" for purposes of the Bank Act, Insurance Companies Act, and Trust and Loan Companies Act. This prevents regulatory overlap.

For compliance officers at Canadian banks, the strategic question is whether to issue stablecoins directly under OSFI frameworks or establish separate entities subject to the Stablecoin Act. Issuing directly avoids the bankruptcy-remote reserve requirement but subjects the bank to OSFI's capital, liquidity, and operational risk standards. Establishing a separate entity subjects it to the Stablecoin Act but provides regulatory clarity and market recognition from being listed on the Bank of Canada's public registry.

Hong Kong does not include a comparable exclusion. Any person issuing a fiat-referenced stablecoin in Hong Kong or pegged to the Hong Kong dollar must obtain an HKMA license, regardless of existing banking licenses. Hong Kong treats stablecoin issuance as a distinct regulated activity requiring specific authorization, even for banks.

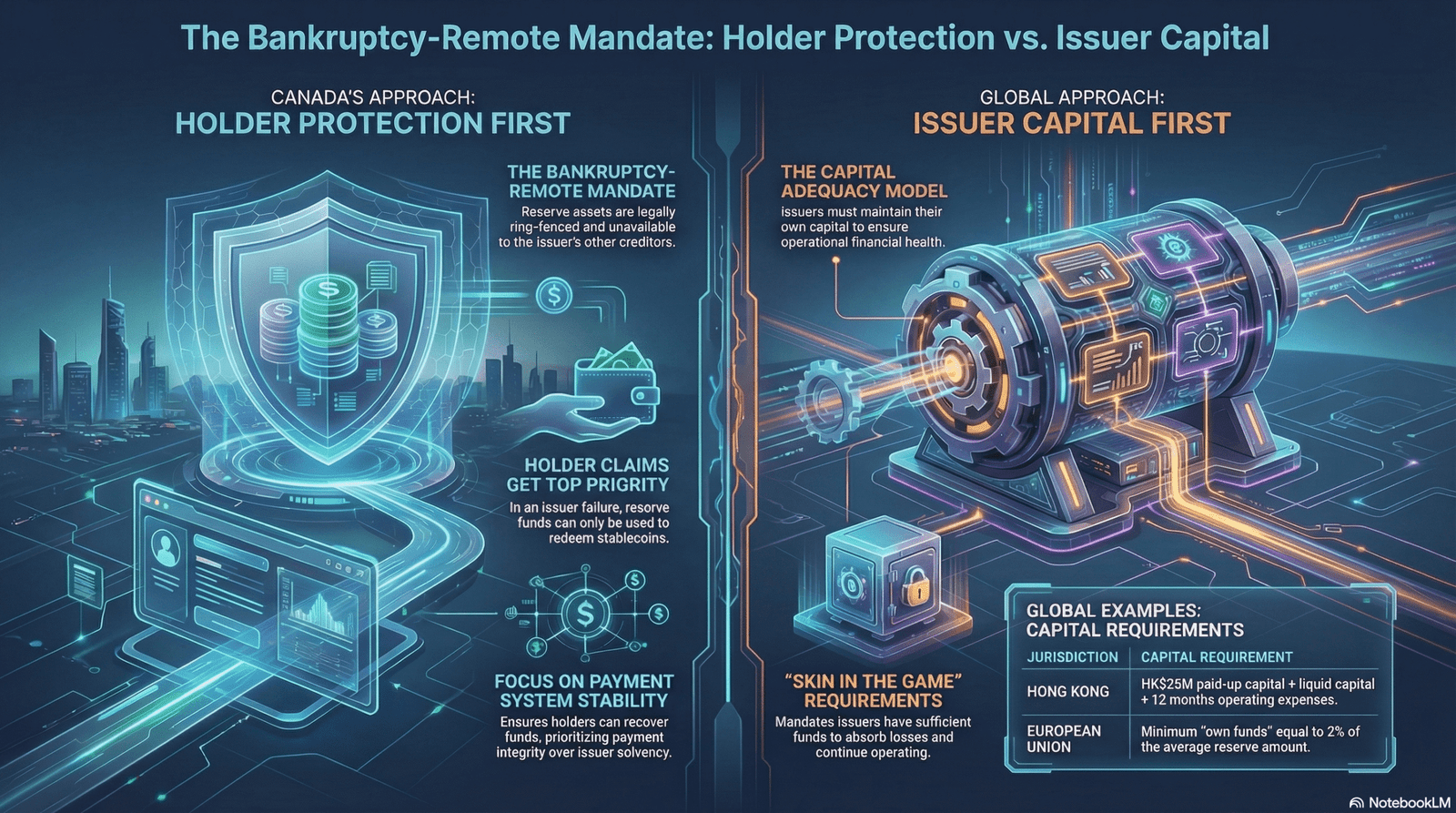

Payment Instrument, Not Investment Product: The Yield Prohibition as Regulatory Philosophy

(Image Generated by Notebook LM)

Section 32 of the Act states: "An issuer must not, directly or indirectly, grant or pay to the holder of a stablecoin that the issuer has issued any form of interest or yield in respect of that stablecoin, whether in cash, digital assets or other consideration." [1] This is not a technical restriction. It is a market positioning mandate that defines how Canada views stablecoins: as payment instruments, not investment products.

The prohibition is absolute. Issuers cannot offer yield "directly or indirectly," whether in "cash, digital assets or other consideration." This blocks structures where issuers invest reserve assets in yield-generating instruments and pass returns to holders. It also blocks arrangements where third parties provide yield to holders as an incentive to hold stablecoins. Section 33 reinforces this by prohibiting issuers from issuing stablecoins that are "a deposit or proof of a deposit" or "insured under a public deposit insurance system."

This distinguishes Canada from jurisdictions that permit or tolerate yield-bearing stablecoins. The US GENIUS Act includes a similar prohibition: Section 4(a)(11) states that issuers cannot pay holders "any form of interest or yield, solely in exchange for holding a payment stablecoin." [6] But the US prohibition is narrower—it applies only to yield paid "solely in exchange for holding" the stablecoin. Yield tied to other activities, such as staking or liquidity provision, may not be prohibited.

Singapore's MAS framework does not explicitly prohibit yield. Instead, it focuses on ensuring stablecoins maintain "a high degree of value stability." [4] If an issuer can demonstrate that yield-bearing stablecoins meet MAS's value stability requirements, they may be permissible. Hong Kong's framework similarly does not prohibit yield but requires that stablecoins maintain a stable value by reference to a fiat currency.

The EU's MiCA framework does not prohibit yield for asset-referenced tokens (ARTs) or e-money tokens (EMTs). However, MiCA classifies yield-bearing tokens differently. If a token offers yield, it is more likely to be classified as a security or derivative, subject to MiFID II or other securities regulations, not MiCA. This creates a regulatory boundary: payment-focused stablecoins fall under MiCA; investment-focused tokens fall under securities law.

Canada's absolute prohibition reflects a regulatory judgment that stablecoins should not compete with bank deposits or money market funds. The Bank of Canada is protecting the traditional banking system from disintermediation. If stablecoins offered yield, depositors might shift funds from bank accounts to stablecoins, reducing banks' deposit bases and increasing funding costs. The prohibition prevents this.

For compliance officers, the yield prohibition creates three operational challenges. First, it requires monitoring issuer arrangements with third parties. If a third party offers yield to stablecoin holders as a marketing incentive, the issuer may be liable under Section 32 for "indirectly" granting yield. Second, it complicates reserve management. Issuers cannot invest reserve assets in yield-generating instruments and pass returns to holders. Section 37(2) states that issuers "must not use the assets in the reserve of assets for a purpose other than to redeem outstanding stablecoins," subject to regulations. This limits reserve investment strategies. Third, it creates competitive disadvantages. If other jurisdictions permit yield-bearing stablecoins, Canadian issuers cannot compete on yield, only on stability and regulatory credibility.

The prohibition also has implications for DeFi protocol integration. If a stablecoin holder deposits stablecoins into a DeFi lending protocol and earns yield, is the issuer liable under Section 32? The Act does not address this. The prohibition applies to issuers, not holders. But if the issuer has an arrangement with the DeFi protocol to incentivize deposits, the issuer may be "indirectly" granting yield. Compliance officers must assess whether issuers have relationships with DeFi protocols that could trigger Section 32.

The yield prohibition is the clearest expression of Canada's regulatory philosophy: stablecoins are payment infrastructure, not investment vehicles. This positions Canada closer to the US GENIUS Act's payment stablecoin model than to Singapore's or Hong Kong's more flexible approaches. It also signals that Canada is prioritizing financial system stability over innovation. The Bank of Canada is willing to limit stablecoin functionality to protect the traditional banking system.

National Security Review: Stablecoins as Critical Financial Infrastructure

Section 21 of the Act grants the Minister of Finance authority to review applications "if the Minister is of the opinion that it is necessary to do so for reasons related to national security." [1] Section 27 permits the Minister to direct the Bank of Canada to refuse an application for national security reasons. Section 74 allows the Minister to prohibit an issuer from issuing a stablecoin "for reasons related to national security or...in the public interest."

This is a geopolitical risk management framework. Canada is treating stablecoins as critical financial infrastructure subject to national security oversight, similar to the CFIUS review process in the United States for foreign investment in sensitive sectors. The Minister's veto power is discretionary and not subject to judicial review under the Act.

Hong Kong's framework grants the HKMA discretion to refuse a license on "public interest" grounds, but the emphasis is on financial stability and investor protection, not national security. Singapore's opt-in framework does not include an explicit national security review. The US GENIUS Act, enacted July 18, 2025, establishes a dual federal-state regulatory system but does not include a standalone national security veto power comparable to Canada's.

For compliance officers, the national security review creates uncertainty. The Act does not define "national security" or specify criteria for review. Applicants with foreign ownership, cross-border operations, or ties to jurisdictions subject to Canadian sanctions face heightened scrutiny. Banks considering partnerships with stablecoin issuers must assess whether the issuer's ownership structure or business model could trigger a national security review.

No Redemption Timeline: Operational Risk Uncertainty

Section 35 of the Act requires issuers to "redeem outstanding stablecoins in the reference currency, at par value and in accordance with the regulations, if any." [1] The Act does not specify a redemption timeline. Section 36 requires issuers to establish a redemption policy describing "the conditions that apply to redemption, including with respect to the manner and timing of redemption and any fees or charges."

Singapore's MAS framework, finalized August 15, 2023, mandates that issuers return the par value of stablecoins to holders within five business days from a redemption request. [4] Hong Kong's framework requires redemption at par with an expectation of immediacy. The US GENIUS Act requires redemption at par but does not specify a timeline; instead, it mandates monthly attestation of reserves.

Canada's undefined timeline creates legal uncertainty. During stress periods, disputes between holders and issuers over "timely" redemption are likely. For banks acting as custodians, the absence of a timeline complicates liquidity planning. A five-business-day standard, as in Singapore, provides a buffer. An immediate redemption expectation, as in Hong Kong, imposes the highest operational burden.

The EU's MiCA framework distinguishes between ARTs and e-money tokens (EMTs). ARTs are redeemed at the current market value of reserve assets; EMTs are redeemed at par. MiCA does not mandate specific timelines, but the distinction allocates market risk: holders of ARTs bear the risk that reserve assets may fluctuate in value.

Canada does not make this distinction. All fiat-referenced stablecoins are subject to the same requirements: 100% backing, bankruptcy-remote structure, redemption at par. Section 32 prohibits issuers from granting or paying "any form of interest or yield in respect of that stablecoin, whether in cash, digital assets or other consideration." This reinforces the payment functionality focus.

Monthly Reporting: Transparency and Ongoing Supervision

Section 46(3) of the Act requires issuers to provide the Bank of Canada with information on "the issuer's financial condition, the number of outstanding stablecoins, [and] the composition of the issuer's reserve of assets and the fair market value of the assets in the reserve" at least once every month. [1] Section 46(1) requires a statement from a certified accountant confirming the reserve satisfies requirements and a statement from a lawyer confirming compliance with the no-encumbrance and qualified custodian requirements.

This is more frequent than Hong Kong's framework, which requires periodic reporting but does not specify monthly intervals. The US GENIUS Act mandates monthly attestation of reserves, similar to Canada. Singapore's framework requires disclosure of audit results but does not specify monthly reporting.

For compliance officers, monthly reporting imposes operational costs: real-time tracking of reserve composition, fair market value calculations, and coordination with certified accountants and lawyers. Banks acting as custodians must provide data to issuers on a monthly basis to support these reports.

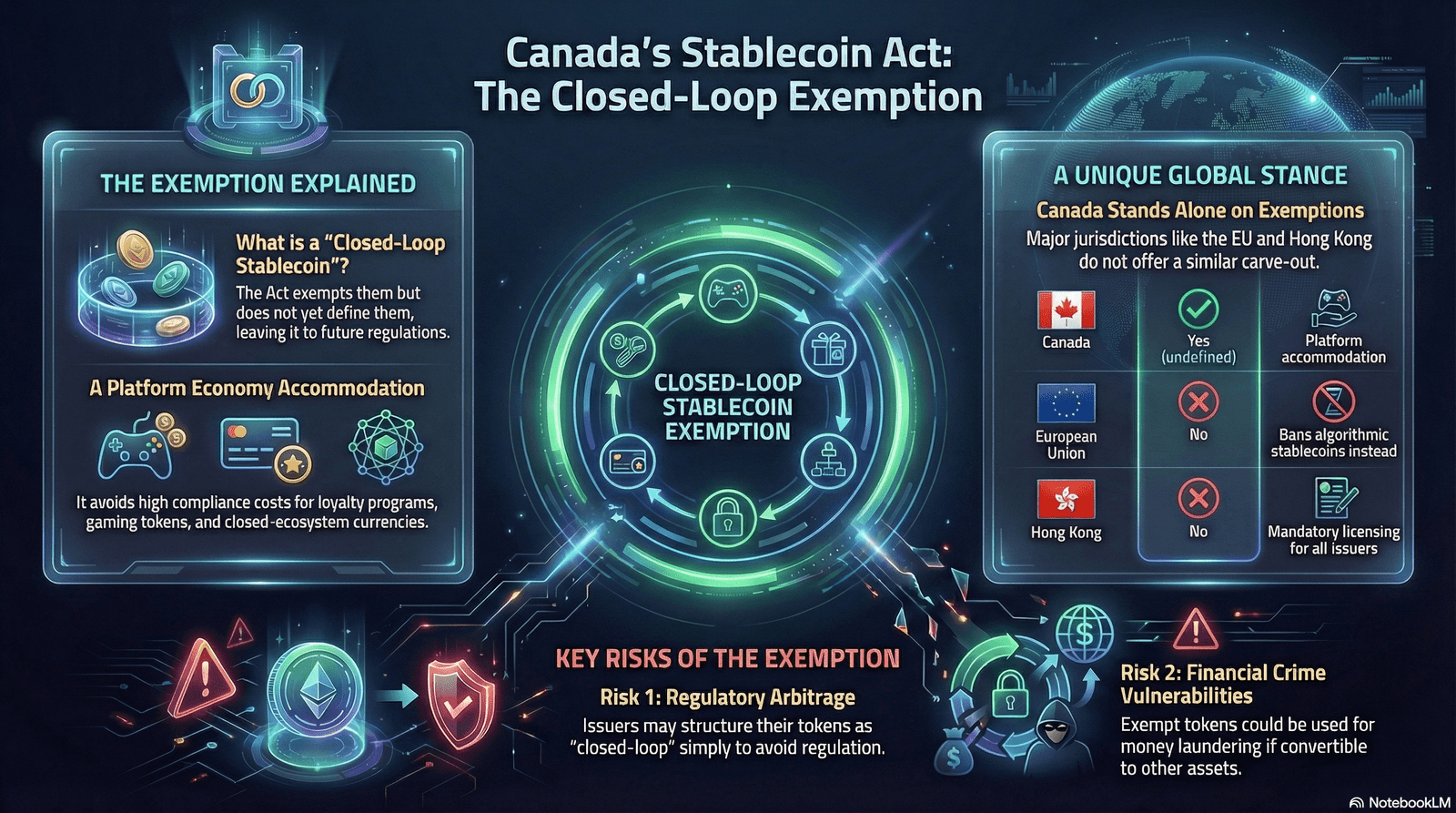

The Closed-Loop Exemption: Platform Economy Accommodation

(Image Generated by Notebook LM)

Section 11 of the Act states: "Subject to the regulations, this Act does not apply in respect of a closed-loop stablecoin." [1] The Act does not define "closed-loop stablecoin"; Section 91(b) authorizes the Governor in Council to make regulations "respecting the exclusion under section 11, including to specify the circumstances in which the exclusion does not apply and to define 'closed-loop stablecoin.'"

This exemption reflects a platform economy accommodation philosophy. Canada is permitting platform-restricted or single-merchant tokens to operate outside the Stablecoin Act, likely to avoid imposing compliance costs on loyalty programs, gaming tokens, or closed-ecosystem digital currencies.

The EU's MiCA framework does not include a closed-loop exemption. Instead, MiCA bans algorithmic stablecoins—stablecoins not fully backed by reserve assets. This reflects a financial stability priority over innovation. Hong Kong's framework requires mandatory licensing for any stablecoin pegged to the Hong Kong dollar, with no platform exemption. The US GENIUS Act defines "payment stablecoins" narrowly but does not include a closed-loop carve-out.

For compliance officers, the closed-loop exemption creates a regulatory arbitrage risk. Without a clear definition, issuers may structure stablecoins as "closed-loop" to avoid the Act's requirements. The exemption also creates financial crime vulnerabilities: closed-loop stablecoins could be used for money laundering or terrorist financing if they are convertible to fiat currency or other digital assets outside the platform.

Cross-Border Operational Friction: Jurisdiction-Specific Compliance Protocols

For banks operating across Canada, Hong Kong, Singapore, and the EU, these philosophical differences translate into operational friction. A bank acting as a custodian for stablecoin issuers in all four jurisdictions must navigate:

- Canada: Bankruptcy-remote reserve structure, no capital requirement, monthly reporting, undefined redemption timeline, national security review risk.

- Hong Kong: HK$25 million paid-up capital, HK$3 million liquid capital, 12 months operating expenses, overcollateralization expectation, immediate redemption expectation, mandatory licensing for all issuers.

- Singapore: Minimum base capital and liquid assets, 5-business-day redemption standard, opt-in framework with MAS label.

- EU: 2% own funds for ARTs, distinction between ARTs (market-value redemption) and EMTs (par-value redemption), algorithmic stablecoin ban.

These differences are not technical. They reflect fundamentally different regulatory judgments about the role of stablecoins, the balance between innovation and stability, and the level of holder protection. Banks cannot use a one-size-fits-all compliance framework. Instead, they must develop jurisdiction-specific protocols reflecting each regime's unique philosophy.

Strategic Implications: Prudential Stability Versus Financial Hub Competitiveness

Canada's prudential-first approach prioritizes systemic stability over financial hub competitiveness. The Bank of Canada is not trying to attract stablecoin issuers; it is ensuring stablecoins do not pose risks to the payment system. This is a defensive regulatory posture.

Hong Kong's licensing-for-market-access model balances investor protection with financial hub competitiveness. The HKMA is creating a safe environment for retail participation while positioning Hong Kong as a leading jurisdiction for digital asset innovation. This is an offensive regulatory posture.

Singapore's opt-in framework is market-driven: issuers seek the MAS label if they want to signal credibility. The US GENIUS Act establishes a dual federal-state system balancing federal oversight with state flexibility.

For compliance officers, Canada's framework is unlikely to attract a large number of stablecoin issuers, but it will impose rigorous standards on those that operate in Canada. Hong Kong's framework will attract issuers seeking retail market access in Asia but requires high capital and reserve standards. Singapore's framework will attract issuers seeking a credibility signal without mandatory compliance.

The Path Forward: Adaptive Compliance Frameworks

Compliance officers should not wait for global harmonization. Convergence is likely on core principles: 100% reserve backing, high-quality liquid assets, redemption at par for fiat-referenced stablecoins. Divergence will persist on structural details: bankruptcy-remote requirements, capital adequacy thresholds, redemption timelines, supervisory regimes.

The compliance challenge is to build adaptive frameworks that accommodate multiple regulatory philosophies simultaneously. This requires investment in legal expertise, operational infrastructure, and cross-border coordination. It also requires understanding the regulatory logic behind each framework—not just the rules, but the principles and priorities that animate them.

Canada's draft Stablecoin Act is not just another regulatory framework. It is a statement of regulatory philosophy that places prudential stability ahead of innovation and market access. For compliance officers, understanding this philosophy is the first step toward building the infrastructure required in a multi-jurisdictional stablecoin environment.

Sources

[1] Parliament of Canada, Bill C-15 (Budget 2025 Implementation Act, No. 1), First Reading, November 18, 2025. https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/45-1/bill/C-15/first-reading

[2] Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, "Canada releases draft framework for stablecoin regulation," December 2, 2025. https://www.osler.com/en/insights/updates/canada-releases-draft-framework-for-stablecoin-regulation/

[3] Sidley Austin LLP, "Hong Kong Implements New Regulatory Framework for Stablecoins," August 5, 2025.

[4] Monetary Authority of Singapore, "MAS Finalises Stablecoin Regulatory Framework," August 15, 2023.

[5] European Securities and Markets Authority, "Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA)," accessed December 5, 2025.

[6] U.S. Congress, "GENIUS Act," Public Law 119-27, enacted July 18, 2025.